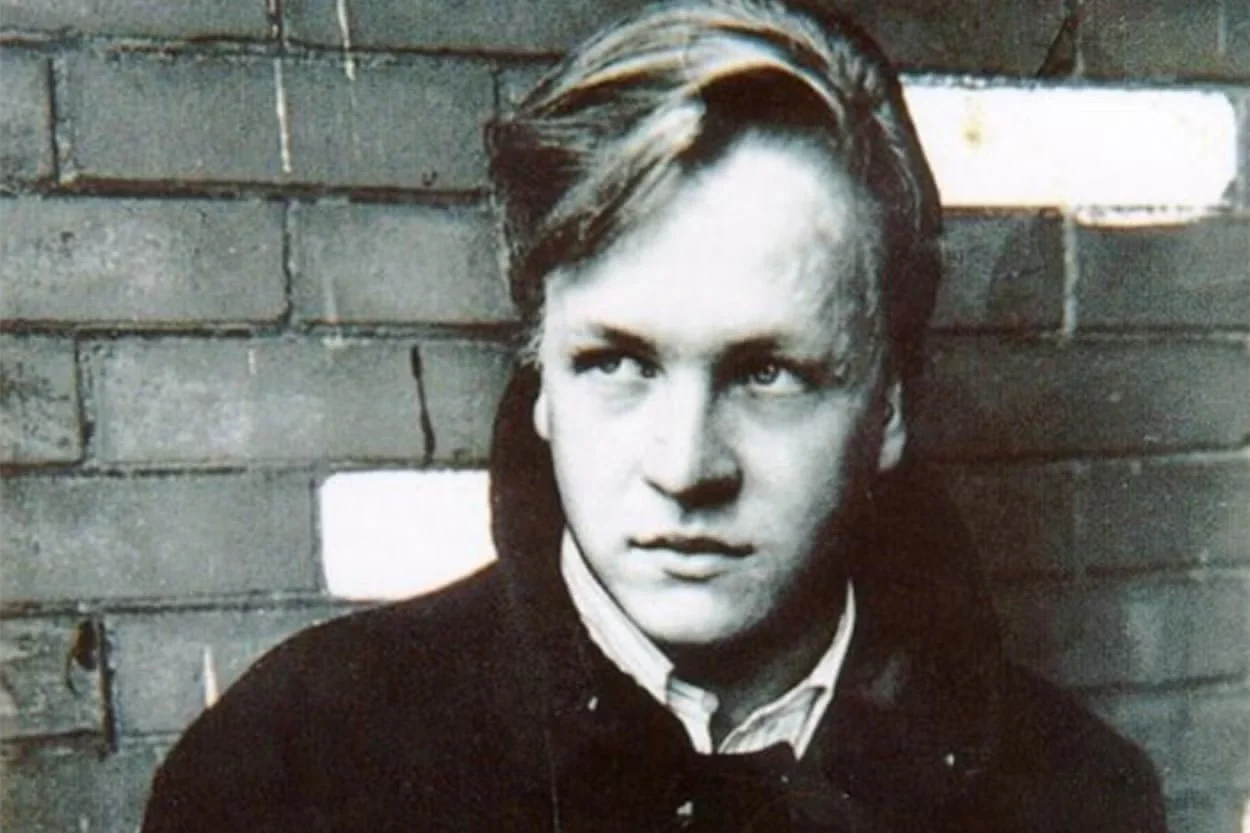

Blues Run the Game: The Haunted Legacy of Jackson C. Frank

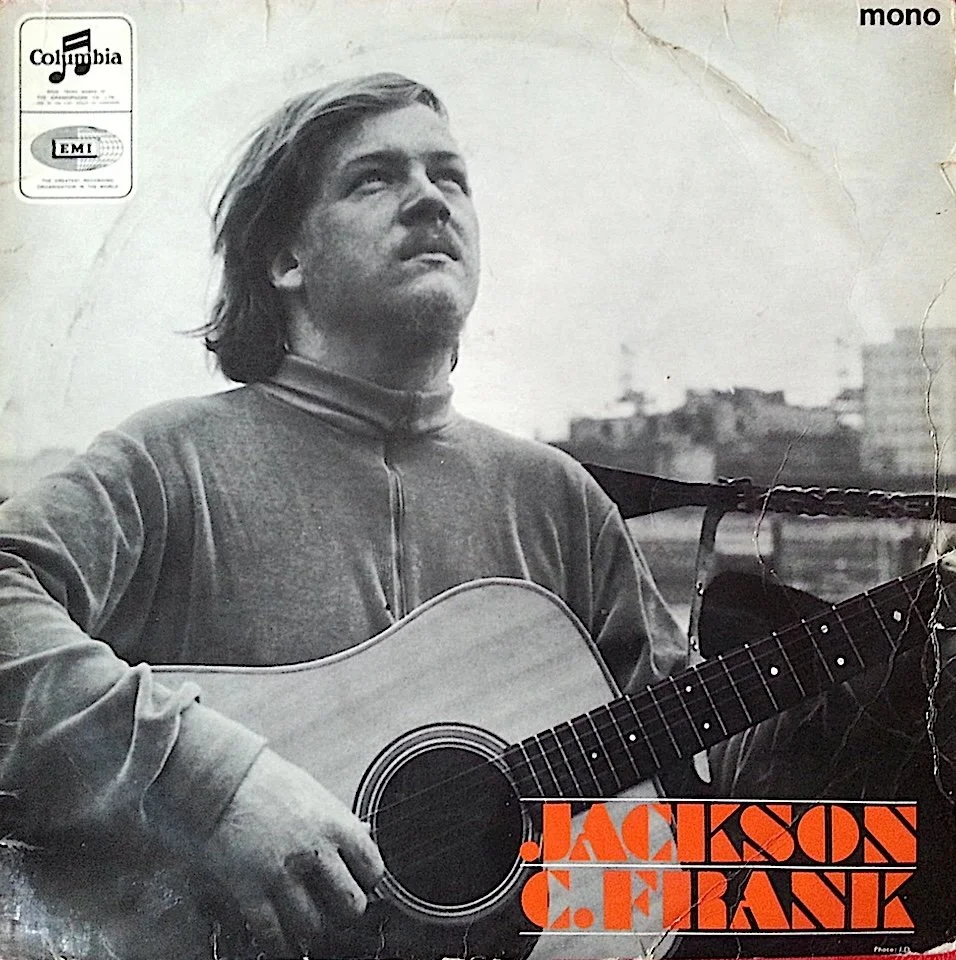

‘Blues Run the Game’ is widely regarded as one of the most significant compositions of the 1960s folk revival. Written by Jackson C. Frank and released in December 1965 on his only album, Jackson C. Frank (Columbia SX 1788), the song quickly became a recognised standard. Its plainspoken melody and stark, unresolved lyric seemed to arrive fully formed, carrying with it the weight of the life behind it. It was written by a tragic young American who had come into sudden money, crossed the Atlantic, and found, for a brief period, a sense of belonging in Soho.

Contemporary critics recognised its importance immediately. Reviewing the album in Melody Maker on Christmas Day, 1965, Karl Dallas singled the song out:

“Certainly, at least one of the original songs on this album, ‘Blue Run The Game’ is all set to become a standard around the blues-oriented clubs… Partly, it may be because Jackson isn’t just putting on a mask of self-pity to win sympathy. He has had a pretty tough time, and the songs are genuine communications of what it felt like.”

Dallas’s prediction proved accurate. The song passed quickly into the repertoire of British musicians and has remained there ever since.

The ‘blood money’ and the Atlantic crossing

Jackson C. Frank’s life had already been defined by catastrophe long before anyone heard him sing. In 1954, aged eleven, he survived a furnace explosion at his school in Buffalo, New York, which killed fifteen classmates, including his first girlfriend, Marlene DuPont. He was left badly burned, and the psychological consequences stayed with him.

He tried to build a life nonetheless. He trained as an apprentice journalist with The Buffalo News and spent his evenings playing folk and blues in local clubs such as the Limelight and the Boar’s Head, singing songs like ‘Plane Wreck at Los Gatos’, ‘Wild Bill Jones’, and ‘3:10 to Yuma’ with a loose group known as the Grosvenor Singers. Yet everything remained provisional, overshadowed by the knowledge that he would one day receive a substantial insurance settlement for his injuries — “blood money for his crippled body”, as his friend Mark Anderson later described it.

When that payment finally arrived, on his twenty-first birthday in 1964, it amounted to $110,500 — more than enough to begin again somewhere else. Frank boarded the RMS Queen Elizabeth bound for Southampton, accompanied by his girlfriend Kathy Henry and a Martin acoustic guitar. According to later accounts, it was during this voyage that he wrote the opening line that would define him: “Catch a boat to England, baby / Maybe to Spain...”

Arrival, retreat, return

Frank’s first months in England were marked less by music than by drift. With money in his pocket and little direction, he became preoccupied with acquiring British sports cars and Martin guitars and took rooms at the Strand Palace Hotel, chosen for its proximity to the Savoy, where Bob Dylan had stayed. He and Kathy travelled widely, spending freely and living, in her words, an “almost matrimonial life”.

The arrangement did not last. When she became pregnant, they returned abruptly to Buffalo, where she underwent an illegal abortion. Soon afterwards, Frank returned to London alone. This second arrival, in 1965, would prove decisive.

Judith Piepe and the East End sanctuary

Back in London, Frank found his way to the East End flat of Judith Piepe, at 6 Dellow House. Piepe was one of the catalytic figures of the Soho folk scene. A survivor of Gestapo torture in Nazi Germany, she described herself as having “the scars of an outcast,” which enabled her to connect with the “disenfranchised” young people she worked with. Her flat became a place of refuge where musicians and outsiders lived side by side. Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, Sandy Denny, and Al Stewart all passed through, alongside the rent boys and homeless youths she supported through her social work.

Through Piepe, Frank was drawn into Soho’s network of clubs and musicians.

The BBC documentary Meeting Point (1966) preserves a brief record of this world. It remains the only known film footage of Frank performing in London and the only surviving film shot inside Les Cousins. It captures both Piepe’s work and Frank’s presence within the scene that would shape his reputation.

The Barge and the first followers

One of the first places Frank performed regularly was the Kingston Folk Club, held on a converted Dutch barge moored at Kingston upon Thames. John Renbourn later remembered it as damp and creaking, populated by serious blues enthusiasts. It was one of the few places where Frank’s style was immediately understood.

Yet the environment also exposed his fragility. David Mercer recalled how he performed close to the doorway so he could leave quickly:

“Whenever Jackson had finished his set, he used to go up the stairs to the open hatch and sit on the deck in the evening air… This enabled him to recover from whatever bothered him.”

These early performances were enough to build a following that soon followed him into Soho.

Soho and Les Cousins

Frank pitched up in Soho in June 1965. It was the first place he experienced anything like sustained recognition, and the place he would later describe as his second home.

The timing was significant. The folk revival itself was in transition. As Karl Dallas later observed:

“It was a time of polarisation when the young Turks were about to wrest the folk revival from the hands of the Old Left pioneers… A reaction against the puritanical neo-Calvinism of Marxists like Bruce Dunnet and Ewan MacColl, for which the new band of what we were later to call singer-songwriters were to substitute something a great deal more hedonistic, instinctual, less rational.”

Les Cousins, on Greek Street, was one of the places where that shift took hold. And at its centre, quietly and without ceremony, was Andy Matheou — one of the great unsung tastemakers of 1960s London.

Andy was not a manager in any conventional sense. He has been described variously as Buddha-like, quiet, stoned, prescient — a curly-headed, beatific figure more often found standing at the foot of the stairs than directing proceedings. He did not impose rules or attempt to shape the music according to any ideology. Instead, he kept the room open, and that openness allowed something new to emerge.

Indian classical musicians appeared there alongside the avant-garde experiments of Ron Geesin, while younger writers including Bert Jansch, Sandy Denny, Nick Drake, Roy Harper, and Cat Stevens were given space to develop their own material. What emerged, gradually and without announcement, was the British singer-songwriter.

Frank is listed 26 times in the club’s chronology between July 1965 and April 1969, and appeared many more times unofficially. But the numbers alone do not explain his attachment to the place. He became exceptionally close to Andy and his family. Letters he later sent from America suggest that he regarded Andy’s parents as his true family in London, and the club as the only place he had ever felt properly anchored.

Writing in Woodstock Week in 1968, as his life was already beginning to unravel, he looked back on Soho with something close to awe:

“Soho is the raging quasar of night light... From it all life radiates and the only spin-off are the hundreds of taxis hustling people home from Cambridge Circus... It is a strange and harlequin place, a country onto itself, fade-away land.”

He continued:

“Soho is the center of a moving and cogent world, the young come there for a good time and learn through many teachers how actually small their lives have been previously. Music is on the upswing all over the world. There has been a revival in folk-form and compositions in England which will yet work its wiles on our listening….and it happened in Soho, in clubs like ‘Les Cousins,’ the largest folk music club in the world.”

Those who encountered him there often remembered him first as a physical presence. He walked with a slight limp, and the scars from the Buffalo fire were still visible on his hands and arms.

Norm Glenard, who saw him several times, recalled: “He always wore his jacket just over his shoulders which I thought was really cool at my tender age.”

Others remembered his reserve. Terry St Clair, who travelled down from the Midlands after seeing his name on the sandwich board outside Greek Street, remembered him as “very shy.” He had come because he already knew the songs. Others arrived without knowing what they were about to hear.

For a few years, in that basement on Greek Street, Jackson C. Frank was not just another visiting American musician. He was part of the fabric of the place.

Recording ‘Blues Run the Game’

In July 1965, Frank entered CBS Studios on New Bond Street to record the songs he had brought with him across the Atlantic. The session was produced by Paul Simon and completed in less than three hours.

He was, by all accounts, almost unable to do it. Overcome with stage fright, Frank refused to play while others were watching. Simon eventually arranged wooden screens around him so that he could perform out of sight. Hidden from the room, he recorded the ten songs that would make up his only album, including ‘Blues Run the Game’.

Nothing about the performance calls attention to the circumstances of its recording. The voice is steady, the guitar unhurried. Yet the conditions under which it was made — alone, shielded, and under quiet duress — would become part of the song’s character. It does not reach outward. It remains self-contained.

Released in December 1965, Jackson C. Frank sold poorly and was soon deleted from the Columbia catalogue. But ‘Blues Run the Game’ began to circulate independently of the record itself. Musicians learned it from one another. It was sung at Les Cousins and in clubs across Britain. As Karl Dallas had predicted in his original review, it became a standard — not through commercial success, but through repetition, memory, and use.

Royal Festival Hall and the turning point

The height of Frank’s London career came on 28 September 1968, when he opened the Festival of Contemporary Music at the Royal Festival Hall. Compered by John Peel, the bill included Fairport Convention, Al Stewart, and Joni Mitchell. Frank walked on alone.

For many in the audience, it was their first sight of him. Chris Jones, who had come to see Mitchell, remembered the effect:

“Jackson C. Frank opened the evening, and I remember sitting there thinking, ‘Who the hell is this guy?’ He blew the audience away. Absolutely stunned them. I went to see Joni Mitchell, but what actually stuck in my head was Jackson C. Frank. The audience went wild for him. I think Al Stewart was a bit sour about it because Jackson upstaged all the other acts that followed.”

When Frank left the stage, Jones hurried back across the river and into Soho. Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick were playing the first session at Les Cousins that night, and not having seen them before, he was keen to catch the tail end of their set.

Frank was already there.

Jones recognised him standing alone at the bottom of the stairs. Only an hour or two earlier, he had been onstage at the Royal Festival Hall. Now he was back in the basement on Greek Street.

When Jones approached him and praised his performance, Frank shrugged it off.

Jones remembered him as looking “like a lost kid.”

Within months, his life would begin to unravel completely.

The descent

In the summer of 1968, Frank had begun the long decline from which he would never properly recover. His marriage was failing. His infant son was born and died on the same day. The insurance money that had carried him across the Atlantic and bought him his freedom was gone.

He returned to the United States and found brief stability working for the Catskills newspaper Woodstock Week. There, behind a typewriter rather than a microphone, he wrote nostalgically about Soho, grasping at the memory of the only place where his life had seemed to make sense. It proved to be one of the last settled periods he would know.

His mental health deteriorated steadily in the years that followed. Friends lost contact, and rumours replaced facts. In 1989, he was shot in the eye with a pellet gun in New York by youths firing indiscriminately, leaving him blind on one side. His final years were spent in institutions and care facilities, far removed from the London basement where his songs had first taken hold.

He died in 1999.

A standard that endured

‘Blues Run the Game’ did not fade with its author. It travelled quickly, first through the clubs of London, and then much further afield.

Frank’s own recording, released in 1965 on Jackson C. Frank, became the source. Within a year, Sandy Denny had begun singing it. She recorded it at home in 1966, aged just nineteen, while still part of the same Soho circle as Frank. She would return to it again in radio sessions the following year, including Cellar Full of Folk, broadcast on the BBC World Service in March 1967. It was one of three of his songs she carried with her, alongside ‘Milk and Honey’ and ‘You Never Wanted Me’.

Bert Jansch also made the song his own. His version helped establish it within the core repertoire of British acoustic guitar music, where it has remained ever since. Al Stewart, who had been present at the New Bond Street recording session itself, later returned to the song, recording it with Jansch for the 1993 film Acoustic Routes.

Others followed. Steve Tilston recorded it. Martin Simpson included a masterful version on his 2017 album Trails & Tribulations, demonstrating how naturally the song had settled into the tradition.

Meanwhile, its reach continued to widen. Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel performed and recorded it, introducing it to audiences far beyond the folk clubs where it began. In later decades, Nick Drake’s private home recording surfaced, revealing how quickly the song had embedded itself among younger writers at the time. Counting Crows carried it into the alternative rock audience of the 1990s, and Laura Marling has since sung it for a new generation.

It also became part of the historical record. In 1975, Karl Dallas included Frank’s original recording on The Electric Muse, his landmark anthology of the British folk revival, placing it alongside the very tradition it had helped to reshape.

Each version extended its life, but none displaced the original.

From the beginning, the song seemed to describe a life already in motion — leaving, arriving, and leaving again. In time, it would outlive its author, and continue that journey without him.

Exactly as Dallas had predicted.

Further Reading and Listening

Books

Jim Abbott — Jackson C. Frank: The Clear Hard Light of Genius (2014) The only full-length biography, written by the friend who tracked Frank down in his later years. It is deeply personal and the primary source for his tragic backstory.

Ian A. Anderson — Alien Water: Six Decades Paddling in Unpopular Music (2025) A vital new memoir from the musician, label owner and fRoots founder. It offers an insider’s view of the 1960s folk-blues scene, including Les Cousins and the interconnectedness of the London and Bristol circuits.

Colin Harper — Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival Essential for understanding the environment of Les Cousins, where Frank was a central figure and influence.

Karl Dallas, Robin Denselow, Dave Laing, and Robert Shelton — The Electric Muse The 1975 book (companion to the 4-LP set) that analysed the shift from traditional folk to the singer-songwriter movement Frank helped pioneer.

Key Recordings

Jackson C. Frank — Jackson C. Frank (Columbia, 1965)

Recorded in a single three-hour session at CBS Studios, New Bond Street, and produced by Paul Simon, this is the original document. His recording established the song’s form and remains its centre of gravity. A decade later, Karl Dallas included it on The Electric Muse (Island / Transatlantic, 1975), formally recognising its place within the folk revival it had helped to shape.

Sandy Denny — home recordings and BBC sessions (1966–1967; released later on The Attic Tracks and Live at the BBC)

Denny was the first to record the song after Frank, taping it at home in 1966 at the age of nineteen and returning to it in BBC World Service broadcasts the following year, including Cellar Full of Folk. It was one of three of his songs she recorded, alongside ‘Milk and Honey’ and ‘You Never Wanted Me’, and her early adoption helped establish its place within the Soho repertoire.

Simon & Garfunkel — studio and live recordings (1960s)

By performing and recording the song themselves, Simon and Garfunkel carried it beyond the clubs of London and into the wider international folk audience, ensuring its survival outside its original environment.

Bert Jansch — Santa Barbara Honeymoon (Virgin, 1975)

Jansch had been performing the song since his earliest days at Les Cousins. When he recorded it ten years later, it had already become part of his musical language. His version helped secure its place within the permanent canon of British acoustic guitar music.

Bert Jansch & Al Stewart — Acoustic Routes (1993)

Recorded for the documentary film of the same name, this version stands as a tribute from two musicians who had been there when the song first entered the London folk scene. Both had known Frank and recognised his importance early on. Their performance is less an interpretation than an acknowledgement — a way of honouring the man and the song he left behind.

Nick Drake — Family Tree (2007)

Recorded privately in the late 1960s, this home recording shows how quickly the song spread through the same folk circuit. It was already passing between university rooms, bedsits, and late-night gatherings, sustained by listeners only a few years behind its author. Drake encountered it early, carrying it with him into his own more private world.

Steve Tilston — Reaching Back (Free Reed, 2007)

Tilston’s recording, released as part of his retrospective anthology, reflects a lifelong association with the song. A regular at Les Cousins during its final years, he encountered it early, carrying it forward as part of the shared repertoire of the musicians who had gathered there.

Counting Crows — Films About Ghosts: The Best Of… (Geffen, 2003, UK edition)

Included as a bonus track on early pressings, this version introduced the song to a vastly expanded audience, demonstrating its movement beyond the folk revival and into modern alternative music.

Laura Marling — “Blues Run the Game” (Third Man Records, 2011)

Recorded at almost exactly the same age Frank had been when he wrote it, Marling’s interpretation highlights the song’s particular hold over young singers. Written at a moment of departure and uncertainty, it has long attracted musicians standing at a similar threshold, finding in it something that feels immediately their own.

Martin Simpson — Trails & Tribulations (Topic, 2017)

A typically virtuosic performance from one of the foremost acoustic guitarists of his generation. Recorded more than fifty years after Frank wrote it, Simpson’s version shows how the song continues to inspire new interpretations, its structure strong enough to withstand — and reward — reinvention.

Various Artists — Les Cousins: The Soundtrack of Soho’s Legendary Folk and Blues Club (Cherry Red, 2024)

This retrospective returns the song to its point of origin, placing it alongside the voices and environment that first sustained it. In doing so, it restores the sense of community through which it first spread, among the musicians and listeners who carried it beyond Greek Street.Forthcoming

Forthcoming

Jon Wilks — Untitled Les Cousins History (Paradise Road, expected 2027) A full-length history of the club at 49 Greek Street, based on archival research and interviews with those who were there.